As a therapist, I proudly identify as an anti-oppressive practitioner. This isn’t just a professional stance—it’s deeply rooted in my values and informs how I work with clients every day.

In this blog I will explore:

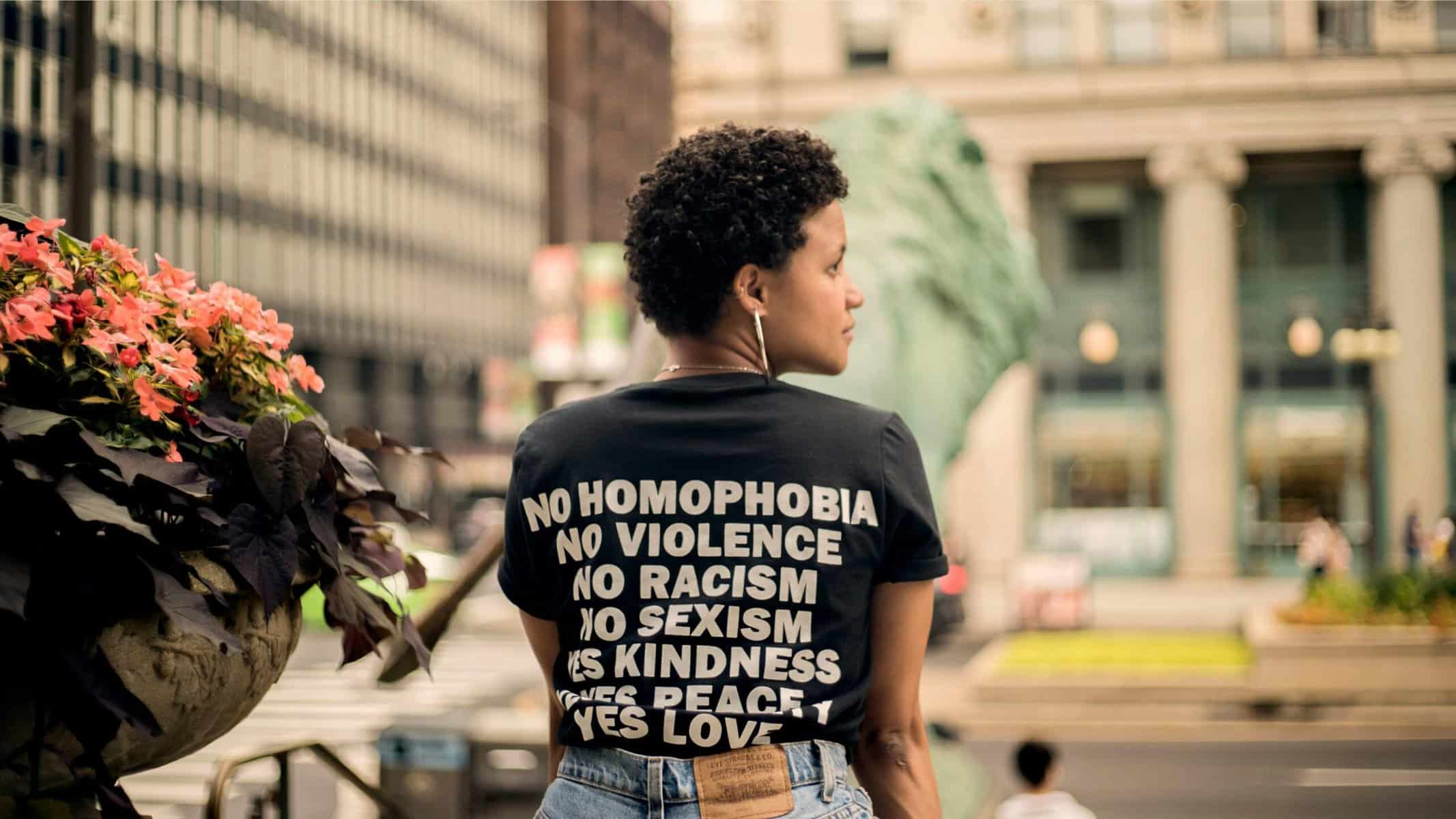

Anti-Oppressive Practice (AOP) originates from social care and challenges systemic inequalities perpetuated by structures like racism, sexism, classism, and ableism. It aims to dismantle these systems to promote equity and justice at every level: individual, institutional, and cultural.

Oppression can be complex, with many forms and layers. For this discussion, let’s define oppression as:

The exploitation of groups of people based on perceived differences, such as race, gender, class, sexuality, or ability.

Oppression functions on multiple levels:

Terms like power and privilege often come up in conversations about oppression. They highlight how some individuals, based on their identity, benefit from systems that others struggle against.

About a decade ago, American science fiction author John Scalzi wrote an article that went viral, introducing a metaphor that has since become a powerful tool in schools and universities to explain privilege. As a straight, white, cisgender, American man, Scalzi framed privilege as the "lowest difficulty setting" in a game called The Real World. His metaphor made the concept more accessible, especially to those who might otherwise feel defensive about discussions of privilege.

Scalzi’s explanation starts with this: in The Real World, you don’t get to choose your character’s "difficulty setting." It’s assigned at birth by the system. If your character is "Straight, White, Cis, Male," then congratulations—you’ve been given the lowest difficulty setting the game offers.

Here’s what that setting looks like in practical terms:

Importantly, Scalzi stressed that calling it the lowest difficulty setting is very intentional—it’s not the same as saying the game is "easy." Life isn’t easy for most people, regardless of their privilege. The "game" has inherent challenges, like economic instability, personal tragedies, or health crises, that affect everyone to varying degrees.

But privilege means not having to contend with certain systemic barriers or biases that make the game harder for others. For example, as a straight, white, cisgender male:

This doesn’t diminish the real struggles that straight, white, cis men face. Many in this group encounter legitimate hardships—such as economic challenges, mental health struggles, or societal pressures to conform to stoic, emotionless masculinity. In fact, such pressures have been linked to higher suicide rates among men in Western countries when compared to their female counterparts (source). These are real and pressing issues that deserve attention and care.

What Scalzi’s metaphor highlights, however, is that privilege isn’t about having an "easy life." It’s about the absence of certain obstacles that others face simply because of their gender, race, sexual orientation, or other aspects of their identity. A straight, white, cis man might experience immense personal difficulty, but those difficulties aren’t compounded by systemic racism, homophobia, or misogyny.

In this context, the "lowest difficulty setting" is a call to understand how societal structures shape experiences differently, depending on who you are and where you start in the game. Recognising this isn’t about guilt or blame—it’s about awareness and empathy for those navigating 'The Real World' on harder settings.

After recognising privilege and its implications, many people ask, “What do I do now?” My answer? Start being an ally.

An ally is someone who actively supports, amplifies, and advocates for people from marginalized groups without being a member of those groups themselves.

Below is a commonly used graphic about becoming anti-racist, which outlines the progression from the Fear Zone to the Learning Zone and finally to the Growth Zone (source). While this specific example focuses on racism, the framework can be applied to other forms of systemic oppression.

Many people equate “not being racist” with not identifying as a racist. However, much like allyship, being anti-racist is not a static identity—it’s an ongoing action. Being anti-racist (or anti-sexist, anti-ableist, etc.) requires deliberate and repeated choices to confront oppression.

For instance, some may think, “I’m not actively harming anyone—so I’m doing enough.” Yet, as the chart shows, remaining in the Fear Zone—where there is a refusal to acknowledge the problem—contributes to perpetuating these societal issues. Simply avoiding overt discrimination is not enough.

This dynamic applies beyond racism and extends to all forms of oppression, including sexism, ableism, classism, and more. Growth comes from recognising that neutrality in the face of oppression often reinforces the status quo—and that meaningful change requires engagement, courage, and accountability.

Being an ally doesn’t require a complete reinvention of yourself. You don’t need a degree in sociology, nor must you attend every protest or read the last 50 years of feminist literature (though those actions are certainly valuable if you're so inclined). Sometimes, allyship starts with simple, everyday choices—like listening without defensiveness or speaking up in the moment.

Take, for example, the owner of Robinsons Traditional Fish and Chips in the UK. This month, a customer left an inappropriate review about a female staff member, and the owner’s response set a firm boundary:

The owner’s actions went viral, but in interviews, he stated that he viewed his behaviour as “normal.” He believed every staff member deserves to feel safe at work. This is an excellent demonstration of the Bystander Approach—a form of allyship where individuals step in to prevent or reduce harm in their communities.

You don’t have to change the world overnight to make a difference. Sometimes, allyship looks like this:

As Martin Luther King Jr. said, “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

As an anti-oppressive therapist, my approach is grounded in deep respect for each client’s individuality while being mindful of how societal structures, systemic oppression, and intersecting identities shape their experiences and challenges. Below are the key principles that guide my practice:

1. Balancing Awareness with Individuality

Each person is unique, even if they share a common identity. For example, three clients who identify as intercountry adoptees may each have vastly different experiences of what that means to them. Anti-oppressive practice requires an ongoing commitment to curiosity and openness, avoiding assumptions, and treating each client as an individual.

At the same time, I remain aware that no one exists in a vacuum. People’s lives, identities, and mental health are influenced by their social conditions, cultural backgrounds, and systemic forces. This dual focus—acknowledging both individuality and the broader context—is central to my work.

2. Understanding Intersectionality

Each person holds multiple, intersecting identities that influence their experiences of power, privilege, and oppression. For example, a client may be a woman of colour, queer, and living with a disability—all of which shape how they navigate the world. By understanding these intersections, I provide support that is tailored to their unique experiences rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach.

3. Practising Cultural Humility and Avoiding Pathologization

Culture plays a significant role in shaping how people understand themselves and navigate the world, and it’s essential to honour these cultural contexts in therapy. Traditional psychological theories have often dismissed or even pathologized cultural norms and experiences.

For example, a 2014 study by Fromene and Guerin titled “Finding the Context Behind the label” highlighted how Australian Aboriginal individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) were often misunderstood. Many symptoms labelled as “disordered” were in fact “consequences of colonization and displacement from Country” and required “specific individual exploration, especially when treatment is attempted.”

Understanding the broader impact of systemic oppression is vital in avoiding pathologization. For example, experiences of racism can deeply affect mental health, often resulting in trauma responses that deserve recognition and support. I explore this further in my blog on Understanding Racism as Trauma.

4. Collaborating for Empowerment

Therapy has traditionally been viewed as hierarchical, with the therapist as the expert. Anti-oppressive practice seeks to dismantle this unequal power dynamic as much as possible. I work humanistically, respecting individual autonomy and collaboratively building the therapeutic relationship.

A significant part of my training focused on understanding emotions and emotional processes. While I have gained expertise in emotions, I am not the expert on my clients’ lives or their experiences of those emotions. Therapy, for me, is not about prescribing solutions but about walking alongside clients as they navigate their journeys.

At its core, anti-oppressive therapy means seeing clients as whole people, shaped by their environments and histories but never reduced to those influences. It means practising cultural humility, collaborating with clients to empower their healing, and always striving to create a space where their identities and experiences are honoured and respected.

Being trusted to be someone’s therapist is a privilege, and my allyship is always ongoing. I am deeply grateful to every client I’ve worked with—from every background—because they have all helped me reflect, grow, and question my own life experiences.

Amnesty International Australia: How to be a genuine Ally

https://www.amnesty.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/205-how-to-be-a-genuine-ally.pdf

Australian Human Rights Commission: Bystander Approach to Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/publications/bystander-approaches-sexual-harassment-workplace

Disability Activist, Hannah Diveny: Being an ally to people with disabilities

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-22/being-an-ally-to-people-with-disabilities/12684064

Diversity Council Australia: Becoming a better ally for inclusion

https://www.dca.org.au/news/blog/becoming-a-better-ally-for-inclusion

Reach Out : What is an LGBTQIA+ ally, and how can I be a good one?https://au.reachout.com/relationships/allyship/how-to-be-a-good-lgbtqia-ally

Human Rights Campaign Foundation: Being an LGBTQ+ Ally

https://reports.hrc.org/being-an-lgbtq-ally#ways-to-show-your-support

March8: Top 10 powerful ways to be an ally for women

https://march8.com/articles/top-10-powerful-ways-to-be-an-ally-for-women

Australian Anti-Racism Kit

https://www.antiracismkit.com.au/self

Guide to Allyship

https://guidetoallyship.com/